TypeScript Isn’t Perfect

As we all should know, TypeScript is less of a language and more of a super advanced linter that allows us to pretend we have type safety in JavaScript. No shade against TypeScript, it’s by far my favorite “language,” but we shouldn’t kid ourselves into thinking that it provides true type safety. Like many other languages, it’s chock full of foot guns and escape hatches that allow you to bypass compiler safety checks (e.g. {} as unknown as User, any, and @ts-ignore to name a few). One other potential foot gun but also really helpful feature, and the subject of this post, is TypeScript’s structural typing system.

Structural Typing

For a quick recap, structural typing means that two types are considered compatible if their structures (i.e., the properties they have) are compatible, regardless of their explicit declarations. This is in contrast to nominal typing, where compatibility is determined by explicit declarations and names. This can be a good time saver in situations where you have a lot of objects that share similar structures and have functions/methods that operate on the shared members of said objects. Take this example:

interface Entity {

id: number;

createdAt: Date;

updatedAt: Date;

}

interface Post extends Entity {

title: string;

content: string;

author: string;

}

interface Comment extends Entity {

content: string;

author: string;

}

function updatePost(post: Post): Post {

// ...do something

return post;

}

function updateComment(comment: Comment): Comment {

// ...do something

return comment;

}We have simple Entity, Post, and Comment interfaces where Post and Comment some properties from Entity. Then we create some simple update functions that allegedly only accept Post and Comment types respectively. Let’s see how TypeScript handles this:

const postOne: Post = {

id: 1,

title: "Hello World",

author: "Kasim Ahmic",

content: "This is my first post.",

createdAt: new Date(),

updatedAt: new Date(),

};

const commentOne: Comment = {

id: 1,

content: "Great post!",

author: "Jane Doe",

createdAt: new Date(),

updatedAt: new Date(),

};

const updatedPost = updatePost(postOne); // Works as expected

const updatedComment = updateComment(commentOne); // Works as expected

const wrongUpdate = updatePost(commentOne); // Good, TypeScript yells at us!

// error TS2345: Argument of type 'Comment' is not assignable to parameter of type 'Post'.

// Property 'title' is missing in type 'Comment' but required in type 'Post'.

So far, so good. We can pass expected objects to their respective functions and TypeScript correctly prevents us from passing a Comment to updatePost. But what if we had two types that were structurally identical but conceptually different? For example, consider the following:

const anotherWrongUpdate = updateComment(post); // Uh oh... No error!

TypeScript doesn’t have an issue with passing a Post to updateComment, but why? The answer is pretty simple; updateComment doesn’t require some concrete type of Comment, but rather an object that contains the same properties of the same types as Comment. Since Post has all the properties that Comment has (and more), TypeScript sees them as compatible. This of course is by design and can actually be very helpful in scenarios like these:

function createdBefore(entity: Entity, date: Date): boolean {

return entity.createdAt < date;

}

function updatedAfter(entity: Entity, date: Date): boolean {

return entity.updatedAt > date;

}

function deleteEntity(entity: Entity): void {

db.delete(entity.id);

}Since our Post and Comment types both extend Entity, and none of the functions care about anything that exists outside of Entity, we can safely pass either type to these functions without any issues. But what if we wanted to enforce that certain functions only accept specific types, even if they are structurally identical? This is where nominal types come into play.

Nominal Typing in TypeScript

In contrast to structural typing, nominal typing requires explicit declarations for type compatibility. This means that two types are only considered compatible if they are explicitly declared to be so, regardless of their structure. TypeScript doesn’t natively support this, but we can simulate it using techniques like branding:

type Branded<T, K> = T & { __brand?: K };

type PostId = Branded<number, "PostId">;

type CommentId = Branded<number, "CommentId">;

interface Entity<T> {

id: T;

createdAt: Date;

updatedAt: Date;

}

interface Post extends Entity<PostId> {

title: string;

content: string;

author: string;

}

interface Comment extends Entity<CommentId> {

content: string;

author: string;

}

function updatePost(post: Post): Post {

return post;

}

function updateComment(comment: Comment): Comment {

return comment;

}

const postOne: Post = {

id: 1,

title: "Hello World",

author: "Alice",

content: "This is my first post.",

createdAt: new Date(),

updatedAt: new Date(),

};

const commentOne: Comment = {

id: 1,

author: "Bob",

content: "Great post!",

createdAt: new Date(),

updatedAt: new Date(),

};

updatePost(postOne); // Success

updateComment(commentOne); // Success

updatePost(commentOne); // Error!

updateComment(postOne); // Error!

// Argument of type 'Post' is not assignable to parameter of type 'Comment'.

// Types of property 'id' are incompatible.

// Type 'PostId' is not assignable to type 'CommentId' with 'exactOptionalPropertyTypes: true'. Consider adding 'undefined' to the types of* the target's properties.

// Type 'PostId' is not assignable to type '{ __brand?: "CommentId"; }' with 'exactOptionalPropertyTypes: true'. Consider adding 'undefined'* to the types of the target's properties.

// Types of property '__brand' are incompatible.

// Type '"PostId"' is not assignable to type '"CommentId"'.ts(2345)

Success! Now even though Post is technically valid where Comment is expected as far as TypeScript is concerned, our branding technique ensures that they are treated as incompatible types since their id properties are technically of different types; one is Number & { __brand?: "PostId" } and the other is Number & { __brand?: "CommentId" }. TypeScript will now correctly yell at us if we try to mix them up, though the error messages can be a bit verbose. This is one of the bigger downsides of this approach and something to keep in mind when deciding whether or not to use it. In some projects however, the added verbosity is a small price to pay for the added illusion of true type safety.

Use Case

Over the past year, I have been working on various projects where I need to interface with C/C++ code from JavaScript. One such project is libwin

. libwin is an ambitious project in which I am attempting to create native bindings for the entire Windows API using the Node API

. In the Windows API, there are many instances where types use the same underlying primitive types but are conceptually different; HANDLE’s being chief among them. A HANDLE is essentially just a pointer (i.e., a number) to some resource managed by the Windows operating system. However, there are many different types of HANDLEs that represent different resources; file handles, process handles, thread handles, etc. Mixing these up can lead to all sorts of issues, including crashes and data corruption.

HWND CreateWindow(...);

HANDLE OpenProcess(...);

HBITMAP LoadBitmap(...);

HMENU CreateMenu(...);

HINSTANCE GetModuleHandle(...);

HFONT CreateFont(...);

// And many more...

When mapping these to TypeScript/JavaScript however, I have to represent all of these different HANDLE types as a bigint. This of course works since you could also take any uintptr_t or uint64_t, cast it to any HANDLE type, and the Windows API would be none the wiser. However, this them opens up the possibility of passing a HWND where a HBITMAP is expected, exactly the kind of issue our nominal typing system can help prevent. By branding these different HANDLE types, I can ensure that they are treated as incompatible types in TypeScript, and thus prevent accidental mix-ups. Or at least attempt to…

type HWND = Branded<bigint, "HWND">;

type HANDLE = Branded<bigint, "HANDLE">;

type HBITMAP = Branded<bigint, "HBITMAP">;

type HMENU = Branded<bigint, "HMENU">;

type HINSTANCE = Branded<bigint, "HINSTANCE">;

type HFONT = Branded<bigint, "HFONT">;With this setup, we can now type our Windows API bindings and let the TypeScript compiler help us catch mismatched types. As is, this works well and is the generally recommended approach for most project but for libwin, we can take it a step further. Notice how the Branded type takes an additional type parameter K that lives in the __brand property and serves as a sort of unique identifier for the type. What’s stopping us from adding another property here?

That’s right. Nothing!

type Nominal<T, U extends string> = T & {

readonly __jsType?: T;

readonly __cType?: U;

};

type JsType<T extends Nominal<unknown, string>> = NonNullable<T["__jsType"]>;

type CType<T extends Nominal<unknown, string>> = NonNullable<T["__cType"]>;

type HANDLE = Nominal<bigint, "HANDLE">;

type HWND = Nominal<JsType<HANDLE>, "HWND">;

type HBITMAP = Nominal<JsType<HANDLE>, "HBITMAP">;There’s a lot going on here so let’s break it down.

First, we have the new Nominal type which is similar to our previous Branded type but now we’ve added a type constraint on the second type parameter U to ensure that it is always a string. Not strictly necessary, but nice to have. More importantly however, we’ve added two new properties to the type; __jsType and __cType which represent the JavaScript type and the C type respectively. We also mark them as readonly to prevent accidental modification. Finally, and this is something we did before as well, we mark them as optional properties so we don’t need to actually have __jsType and __cType properties at runtime. This does require us to use NonNullable every time we extract these types but that’s what we have the utility types for.

The utility types, JsType and CType, are there to make extracting the underlying types easier. We can see this in use in our new HANDLE types where we define a base HANDLE as a bigint and then define our other HANDLE types in terms of the JsType of HANDLE. This way, we define the underlying C type once and reuse it for all the other types.

Drawbacks

Verbosity

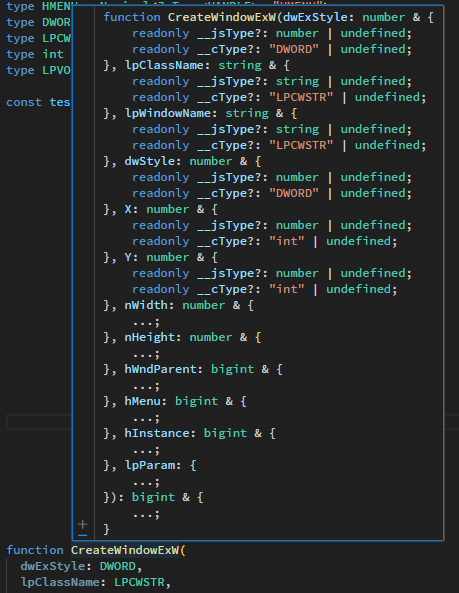

As mentioned before, one of the bigger drawbacks is verbosity. Take a look at the VS Code tooltip for an example implementation of the CreateWindowExW function from the Windows API:

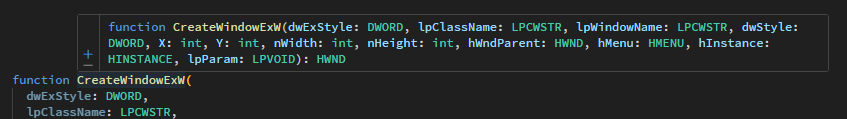

This has actually gotten better in more recent versions of VS Code where you can collapse the type information and just show the name.

This is great for those that are already familiar with the Windows API and know what hell a LPCWSTR is for example, not so much for those that aren’t. Additionally, even for those that are familiar with the various Windows types, they still need to know the underlying JavaScript types sometimes which means we’re back to the expanded view which is kind of a pain to read. Not the end of the world or anything, I mean we’re software engineers after all, we deal with complexity on a daily basis. But it’s something to keep in mind nonetheless.

More Illusion of Safety

As with all things TypeScript, this is still just an illusion of true type safety. At the end of the day, all of these branded/nominal types are just bigints in JavaScript and can be easily mixed up if one were to use type assertions or other escape hatches. If you respect the language and the compiler, it can catch a lot of bugs ahead of time but as soon as you start down the path of “I know what I’m doing,” there be dragons.

Conclusion

With this setup, we can now have the best of both worlds; strong nominal typing to prevent accidental mix-ups, and the ability to easily extract the underlying JavaScript and C types when needed. This is especially useful when writing bindings where we need to convert between JavaScript and C types frequently. Now it should be said that the majority of projects won’t have much use for this as you’ll often only increase complexity and verbosity for minimal gain. However, for some super edge case projects made by people who have more time than sense, this technique has the potential to be quite useful.

Postscript

Hey, thanks for reading! This topic has been covered multiple times by multiple people in the past but I needed a subject for a sort of “test” blog post and my Windows API binding variant seemed interesting enough to write about. In the coming months I’ll be writing more about the libwin project as a whole, so stay tuned!